Segregation, integration, & inclusion. Part 1

My [& Mother’s] Fight for the Right to be Educated

In the 1960s parents of disabled kids in Britain had only two options ~ send their child to a ‘special school’ or have them taught at home.

My special school was called Greenbank School for Rest and Recovery. The name says it all. It was run by the National Health Service, not the Education Department. Most special schools weren’t schools as such, they were really places of containment. Or rather dumping grounds — to hide disabled children away from other children, out of sight from society and also perhaps to give a little bit of respite to parents. Some of the pupils at Greenbank were boarders, who slept in a large dormitory with rows of identical beds — but, thanks to my parents, I went back home every day. We were however usually all put to sleep during the afternoons, via little blue pills that they dished out. My friend has a better memory of those early years than I do, presumably because she didn’t swallow the pills, but instead hid a stash of them under the playground slide.

I’m no expert, but I’m guessing that this practise might be considered to be illegal today.

An education was thus not on the list of priorities at the special school and it was rare for children to sit for any examinations that could provide qualifications for any kind of employment. After all, disabled children like me, were almost invariably written off as unemployable.

I have very few memories of Greenbank. But I remember one of the ‘care’ staff plonking me on the toilet and saying she would return in a few minutes. She was gone for ages and ages….. and ages. I just stared at the cubicle walls. Being four years old I had no sense of time but it seemed like a lifetime before she returned. It could have been an hour or perhaps even longer. I know she was very apologetic when she finally came back and I heard her admitting to a colleague over her shoulder “ooh, I’ve forgotten about this boy, I left him on the loo!” she shouted gayly and I heard her fellow worker laughing. For some reason I’ve always felt a bit claustrophobic and I never close the door to my office when I’m in there alone.

Greenbank was just over 9 miles from my home. I was taken there by taxi every day, driven by a kindly old man called Bill. Almost everyone is old when you’re only five, but he was in his sixties when he first started taking me to school. He would continue to do this until I was about thirteen, when he finally retired. He drove very cautiously at a speed that felt like 5 miles an hour. The journeys seemed to take hours. A lady called Helen [who was around my Mother’s age] would accompany me as a safety escort — her job was to make sure I arrived unharmed and that I didn't fall off the seat (no seatbelts were fitted). She would carry me to and from the vehicle.

a clip from the documentary ‘World In Action — A Day in the Life of Kevin Donnellon’ Granada TV, 1972

The word ‘special’ might seem benign and lovely — after all we see it on greetings cards such as ‘To My Special Wife’ or ‘To A Special Son’ etcetera, but to me the word ‘special’ meant being kept apart. Special schools, special busses, special needs — meant, in reality, being separated from mainstream schools, being unable to access regular public transport and generally being treated differently within a society that has an ‘able bodied’ outlook. Of course, I couldn’t articulate or even understand this as a young child (that came much later in life, when I discovered the Social Model), but I still had an uncomfortable feeling and was confused as to why I couldn’t go to the local school, where my brothers and sisters all went to.

Under the law at the time the schools didn’t even have to give any excuse or provide an explanation for excluding disabled kids. They could [and did] just simply denied entry. The nearby infants and junior school near my home was single storey, all on the ground level, so physical access wouldn’t have been a major issue.

In her younger days Mother was a devout Catholic, attending Mass regularly and doing her religious duty to the RC church by having six children by the age of thirty-five. My two older brothers were both altar boys. But she becamedismayed and disillusioned by the negative, uncompromising attitude of the local Catholic school.

My mother was a bit of a paradox in many ways in that she was very pessimistic and negative about my future, but she nevertheless realised that I was intelligent and knew that I would not receive an adequate education in a special school.

Mother realised that if I stayed in Greenbank I would not have got anything like an even basic formal education and so she wrote a letter to the local newspaper, the Liverpool Echo, which they duly published.

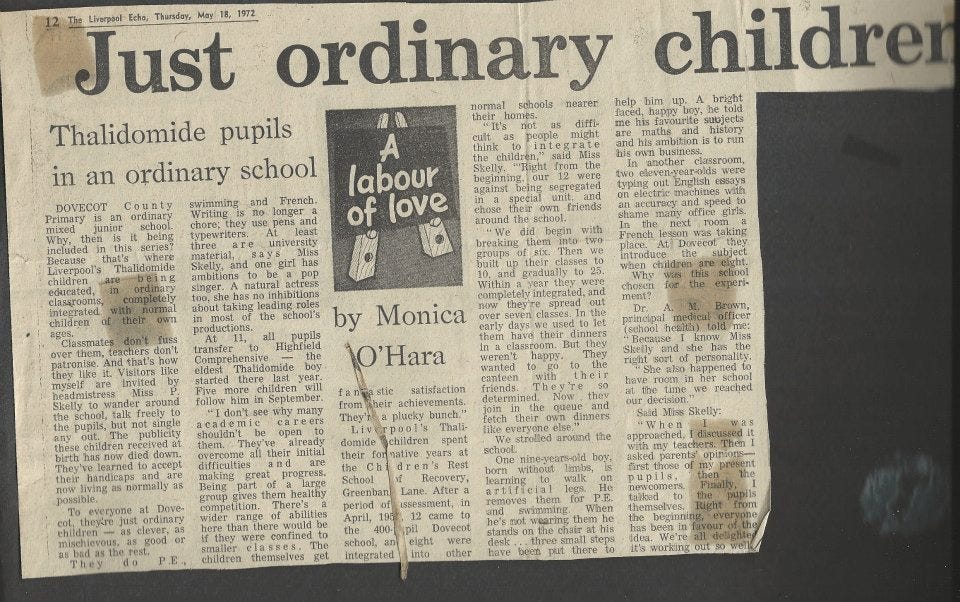

The above photograph is of Miss Pauline Skelly, who was Headmistress of Dovecot Primary school, Liverpool. Pauline Skelly read the letter that my mother wrote, then held a meeting with staff and parents at her school to inform them what she had determined to do and she then drove to Greenbank ‘school’. Entering the ‘classroom’ she saw me playing on the floor with some toys and was told she might as well leave me there as I was ‘the worst of the lot’. Pauline said “Kevin comes with me, or none of them do”. She was a formidable and very assertive lady.

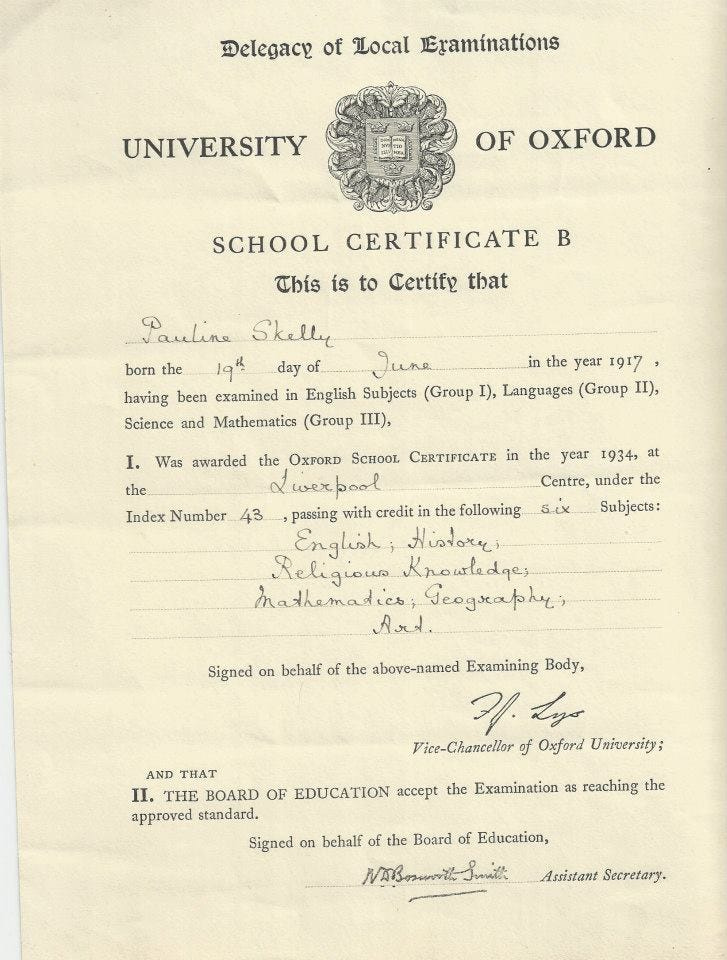

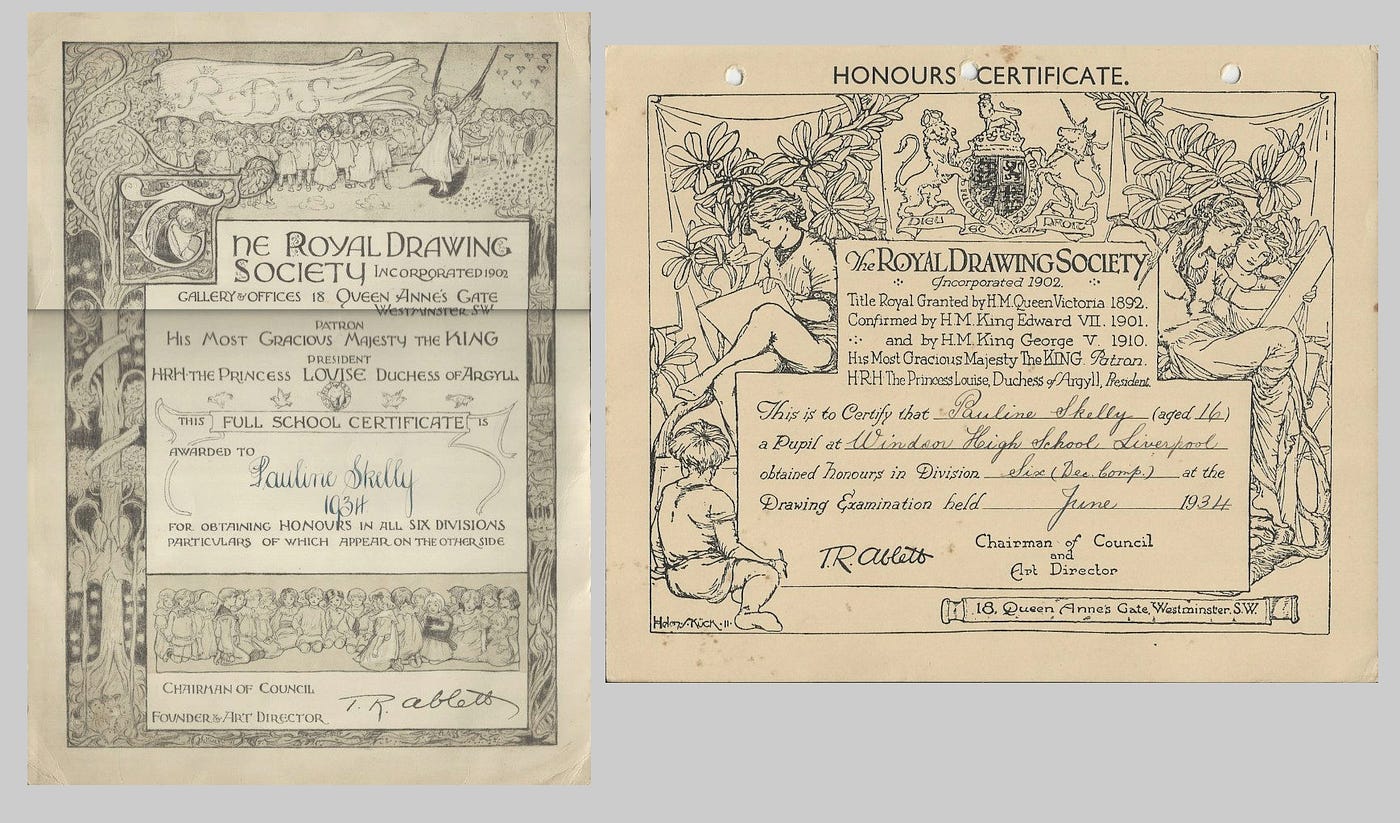

When I first heard this a lump formed in my throat. The reason I know about it is that she left an archive of her life — all in one battered old suitcase. In it was an historical treasure trove which included a scrapbook of photographs from her time at the school dating from 1961 [the year of my birth], and various other documents until her retirement on 31st August 1977, her school certificate from Oxford University, exquisite watercolour paintings [there are certificates from the Royal Drawing Society, dated 1934], letters of commendation from Liverpool Education Authority, farewell cards handmade from some of her adoring pupils and various documents such as a bank loan for the value of £500 in 1960 to purchase a car. Practically her whole life was in that case.

Thalidomide victim recalls kindness of pioneering Liverpool headmistress

A Thalidomide victim who went on to earn a degree, have a child and is soon to be married has spoken of how a very…

Also included were boxes of coloured photograph slides with a small slide viewer. Last (but certainly not least) of the items were three boxes of home cine film. I didn’t own a projector for the old Kodachrome 8mm film, but I couldn’t wait to see what was on them. I took them to my local photographic shop and they sent the three reels to their lab to convert and transfer them to DVD discs.

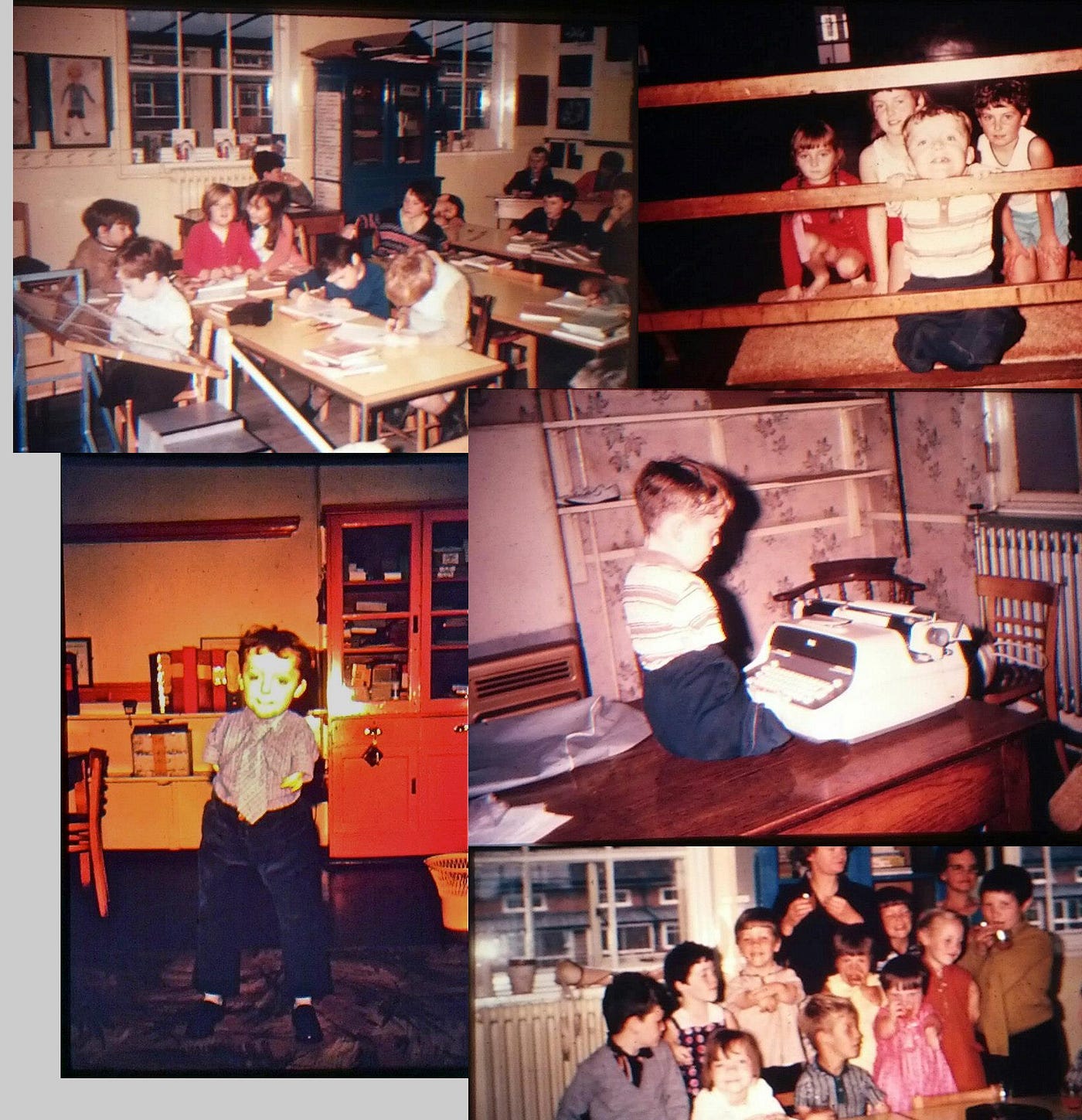

It took a fortnight for them to be processed and returned, but it was worth the wait. All the films were silent, but even so they brought back so many memories of my early days at school. The first film featured a school trip to London. Only one or two Thalidomiders were on this as it was Year Two (being one of the youngest I was in Year One).

The second film showed some of us arriving at school, either by taxi or minibus.

My older sister Joan is an administrator in a local primary school and she was delighted to see the old film. But she couldn’t help laughing about how lax the rules were in those days and she declared that “they’ve broken at least half a dozen health and safety rules” in that one short film alone. For example I’m physically handed over from the taxi to the school nurse Mrs Bailey who carries me almost horizontally to the door, whilst I’m wearing my false legs. I didn’t weigh very much as a child, but those legs weighed a ton — being made of wood, metal and leather [see Pleased to meet you…. part 2 for further information about these awful false limbs].

You can also see a young girl walking on her false legs [her arms are slightly longer than mine so she could usually save her face from hitting the ground if she fell forward] and then struggling by herself with the door and the concrete step. Straight after I arrive a young woman is carrying my school friend Johnny to the door, only this time he is held vertically. Johnny has regular length arms but born without legs. Did you spot the driver of the mini bus holding a prosthetic arm, for the boy walking with an artificial leg?

The final film was sports day. Dovecot had a huge playing field and the whole school took part, including, of course all of us disabled pupils.

I’m the one crawling up a wooden bench that had been brought outside from the gym. I don’t recall who the girl is but she seems very attentive, making sure I don’t fall off, bless her. Did you spot the girl who won the sack race, despite having no arms to hold up the sack?

clip from World In Action “A Day In The Life Of Kevin Donnellon” Granada TV/ITV (1972) — you can hear how heavy they are as I walk across the wooden floor

Miss Skelly retired to the Isle of Man and in her last years the neighbours looked after her. Pauline was never married [that was a condition upon taking the post of headmistress in those days] but she kept referring to ‘my children’. She was talking about us Thalidomiders.

For some reason the only name she could remember was yours truly. When she died in 2011 aged 94, her neighbours contacted the Thalidomide Trust asking if they had a beneficiary called Kevin from Liverpool, which is how I came into possession of her personal archive. This is such a unique and important part of the history of not only Thalidomide, but also the history of integration of disabled children in mainstream schooling and also the history of a remarkable pioneering woman. As such it needed to be somewhere that it would not only be safely kept, but also properly curated and made accessible to anyone interested in researching this subject. So I handed it all over to the Thalidomide Society, where eventually it will probably be displayed at the Wellcome Trust museum, London.

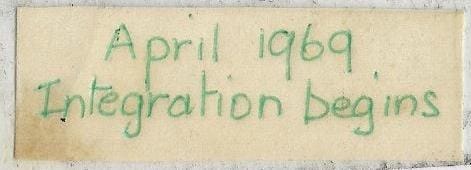

Miss Skelly took thirteen of us (all fellow Thalidomiders) to her school in Dovecot, which was 12 miles away from where I lived. It was April 1969 when integration began in Dovecot.

clip from World In Action “A Day In The Life Of Kevin Donnellon” Granada TV/ITV (1972)

It is important to recognise that Miss Skelly and Dovecot were pioneers of integrated education for disabled school children in mainstream schools in Britain. The school had very little outside professional help or expert support, much of the innovations were trial and error.

I had modified desks, one tilted at different angles and another which included wooden steps up to the bench [see pic. above] that I would climb up, when I wasn’t wearing my crappy artificial legs. I took part in almost all school activities, as well as extra curricular fun stuff such as swimming and pony riding. My pony was called Toby and a young woman sat behind me in the saddle holding me around the waist whilst I held the reins. I’ve always had a thing for jodhpurs for some reason.

more photos from the projector slides. In the archive of the Thalidomide Society.

*************************************

All my posts are now free to read on Substack whether you’re a member or not. If you would like to buy me a coffee it will be so appreciated and you can do so through my Ko-fi Account thank you! :)

Visit my website kevindonnellon.com

A moving and important document Kevin, thank you.